“A collapse in stock markets, co-ordinated policy statements and emergency interest rate cuts: the events of the past week have inevitably led to comparisons to October 2008. But the differences are as significant as the similarities. To understand why it’s helpful to think about the underlying economic forces that are at play.

The crisis of 2008 was, in essence, what economists term a “balance sheet” recession. House price bubbles inflated earlier in the decade and when they subsequently burst, the hole in households’ balance sheet forced a collective shift towards saving (i.e. paying down debt) rather than spending. This in turn exposed vulnerabilities in a highly-leverage banking system. As counter-party confidence collapsed, the financial plumbing froze up. All of this manifested itself in a collapse in aggregate demand.

In contrast, the shock posed by the coronavirus affects both the supply- and the demand-side of the economy. Factory shutdowns, travel bans, supply-chain disruptions and school closures represent a supply shock – the ability of the economy to produce goods and services is diminished. But fewer trips to shops, restaurants and cinemas represent a demand shock – consumer spending falls. Large falls in the stock market also feed into weaker demand by reducing household wealth. These effects can be self-reinforcing, since factory shutdowns can reduce the income of workers, which in turn reduces spending.

In other words, the crisis of 2008 was a financial shock that affected the demand side of the economy. The crisis of 2020 is an economic shock that affects both the demand and the supply side of the economy. The two situations are fundamentally different. This has three implications for what is likely to follow.

The first relates to the shape of subsequent downturn. The 2008 crisis led to a deep recession followed by an extremely slow recovery as households and financial institutions repaired their balance sheets. The coronavirus shock is likely to trigger large falls in output in the affected economies over the next quarter but, provided that the virus fades, activity should rebound as supply constraints are lifted. The outlook is unusually uncertain but our sense at this stage is that this is most likely to be a short, sharp shock.

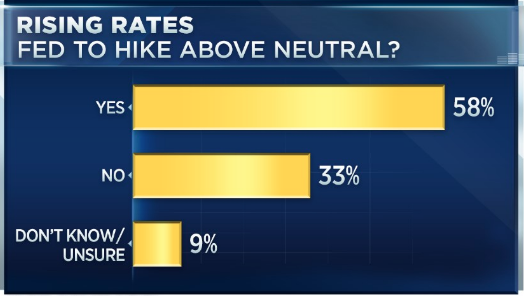

The second implication relates to the role that policymakers can play in cushioning the downturn and stimulating a recovery. Policy stimulus – both fiscal and monetary – works by stimulating demand. It therefore had a clear role to play in 2008. But its role today is less obvious. Targeted, temporary and large fiscal support in the form of loans and subsidies to the hardest hit firms can help to mitigate the shock form the virus, and monetary support can help to counter some of the financial effects. Central banks could also offer cheap finance to banks lending to the most affected sectors. Regulatory forbearance may also help to mitigate any strains in the banking sector. But the speed of recovery will depend in large part on how the virus spreads and when the containment measures are lifted and life returns to normal.

Finally, the worst-case scenario today looks different from in 2008. Economic history shows that the most severe depressions tend to be caused by asset price collapses. In 2008, these effects were magnified by high levels of leverage in the banking system and vulnerabilities in the global financial system (dependence on wholesale finance, short-term credit lines and so on). Debt levels remain high today but are concentrated in less risky areas (government sector rather than households). Meanwhile, banks are better capitalised. Pockets of risk exist – particularly in the corporate sector – and some of these vulnerabilities in the energy sector may be exposed by the sharp drop in oil prices over the past day. But we don’t think these are large enough (yet) to trigger a global crisis.

All of this means that the most likely worst-case scenario today is a sharp but probably short recession rather than an outright depression. As the virus spreads, there’s a good chance that that “worst case” scenario quickly becomes the most likely scenario. But the legacy of the virus beyond the next 6-12 months is uncertain.

One possibility is that it takes the developed world one step closer to full-scale “Japanification”. Another possibility is that interest rate cuts heighten the risk that a hunt for yield in an environment of low returns eventually causes bubbles to inflate, which in turn sows the seeds of the next major crisis. It remains to be seen how events will play out, but it’s increasingly difficult to escape the sense that this is the biggest risk hanging over the global economy beyond the coronavirus.”

Our short-term outlook (through June 2020)

- We are now seeing the third wave of the coronavirus. The first wave was in China’s Hunan province, which remains the epicenter of the disease. The second wave was broader China. The third wave is around the world, focused primarily in Europe, the Middle East, and South Asia.

- The progression of the disease shows that it can be contained: According to data collected by Johns Hopkins University, China currently has 80,556 cases confirmed, but the number of recovered people went from 18,200 on February 20 to 55,700 on March 6, while the number of new cases rose by only 5,556 over the same period.1

- Yet, until we can see the peak in cases outside of China, global equities are likely to retest lows from summer 2019 (2850 on the S&P 500 Index). If recession risk increases, the next support for equities could be the lows from early 2018 (2600 on the S&P 500).

- The coronavirus crisis is unlike most economic shocks. The virus both crimps and slows the flow of goods around the world, and it slows buying as people join quarantines.

- We believe the U.S. economy will avoid a recession, but some additional slowing is likely. We have lowered our U.S. and international economic and earnings forecasts accordingly. Additional changes – higher or lower – will depend on the spread of the virus.

- Stimulus may boost confidence but will require time to work and should be appropriate.

- One risk is that policymakers may not manage market expectations properly around the size and timing of stimulus. Markets are building expectations for stimulus, and any disappointment could add to risk aversion.

- Coordinating stimulus across countries could support global trade, but these efforts so far are missing.

- Another risk is that companies with riskier balance sheets may find more difficulty extending their credit lines. Federal Reserve and fiscal policy could help by targeting low-cost loans to businesses most directly affected, creating a holiday from payroll taxes, and directing spending into the economy. However, these measures have limitations. They take time to work and they treat the economic symptoms of the disease; they do not, by themselves, stop the spread of the disease.

Our medium-term outlook (through year-end 2020)

- The virus may not be eradicated but may be contained, provided testing improves.

- We expect the advanced economies of North America, Europe and the Pacific Rim to contain the virus more effectively. These countries have no region like Hunan province, where the virus spread unconstrained. Also, the citizens of these countries tend to trust government more, which should reduce the uncertainty and fear impact. (Contrast that with Iran, which is limiting information.) The advanced economies also have better medical resources to react and to cope.

- As the virus becomes contained, stimulus measures can have more impact. Rebounds typically are strong from events that create sudden seizures in economic activity (e.g., after the Japanese tsunami of 2011).

- Conditions may be slower to recover in China, Europe and Japan than in the U.S. The former group of economies were weakening significantly even before the coronavirus. The U.S. was relatively stronger.

Our guidance seeks to limit risks but is consistent with further—albeit slowing—economic growth

During periods of strong financial market risk aversion, we believe patience and a proactive approach to managing risk are essential tools. We favor using these tools to stay resilient amid strong cross-currents in the news.

- We believe it is time to move money from fixed income to equities, specifically to U.S. Large Cap and U.S. Mid Cap equities from short-duration fixed income.

- We see relatively greater risk in U.S. Small Caps and Emerging Market equities.

- We continue to favor cyclical or growth-oriented sectors, but those that have stronger quality attributes – including the Information Technology, Communication Services, and Consumer Discretionary sectors.2

- We remain unfavorable on those sectors—Energy, Industrials, and Materials—where inferior quality and impact from the coronavirus leave expected risk larger than prospective reward.

- We have maintained duration in the fixed income portfolios and would underweight Small Cap, Emerging Markets and High Yield.

GS: we need a big US fiscal stimulus boat…

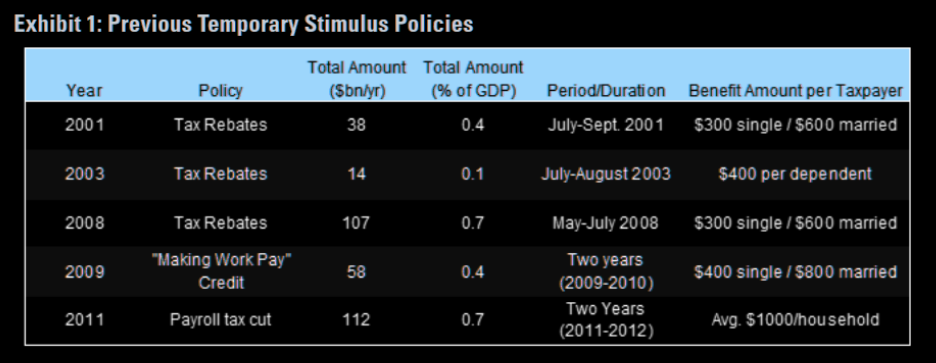

The probability that Congress enacts fiscal measures in response to coronavirus concerns has increased. Tax rebates and policies aimed at ensuring credit availability to small businesses are likely to become priorities for Congress, in our view. Temporary corporate tax provisions also look likely.

The composition and amount of stimulus would depend on economic and virus-related developments over the next couple of months, we believe. If the economy follows our baseline forecast, in which the virus reduces Q4/Q4 growth in 2020 by around 1pp, we expect that discretionary fiscal measures might total around 0.4% of GDP. However, the downside risk to our baseline forecast has increased, and if the economic effects of coronavirus are more negative than expected, fiscal measures could total as much as 1-2% of GDP.