It was another uneven trading day on Wednesday, but all 3 major averages finished in the green, led by the Nasdaq (NDX), which was higher by nearly .7% on the day. One of the sentiment headwinds for equities may have been removed for the next several months, but the market’s strong YTD performance will still hinge upon the strength or weakness of Q1 2019 earnings. But before we discuss earnings any further, let’s get straight to that formerly mentioned headwind removal.

European Union leaders and the U.K. government have agreed to a “flexible extension” of the Brexit deadline until Oct. 31. Donald Tusk, president of the European Council, said this development provides an “additional six months for the U.K. to find the best possible solution.” The extension also contains an option to leave earlier if the prime minister is able to secure the support of the British parliament for her Brexit deal. Tusk didn’t rule out a further extension if the political deadlock in London continued.

French President Emmanuel Macron, who had maintained pressure on Britain throughout the negotiation in Brussels on Wednesday, said leaders had found “the best possible compromise” because October 31 preserved EU unity, allowed the British more time and preserved “the good functioning of the European Union”.

“What we have agreed tonight means that we can leave the European Union before June 30. What we need is to ensure that we have an agreement in parliament, that we can get through the necessary legislation to enable us to leave. This decision enables us to do that,” May told a media conference that started after 2 a.m. local time.”

How does the U.K. affect the U.S. and more importantly trade between the U.S. and the European Union (EU)? American businesses have preferred to use the U.K. as their main gateway to Europe. Since the EU was set up in 1993, U.S. companies have opened subsidiaries and gained strategic partners in the U.K. to do just that.

As a result, the U.K. is the No. 1 destination for U.S. goods and services within the EU and the second-biggest recipient of American investment.

One of the reasons London became the EU’s largest financial center — and the primary conduit to Europe for U.S. banks like JPMorgan Chase (JPM) and Goldman Sachs (GS) is because of something known as “passporting.” Passporting allows a company granted regulatory permission to undertake certain activities in one member state to do the same business in every other EU country. In practice, this has meant a U.S. financial company could simply open up an office in London to have access to the entire market. U.K.-based employees were then free to work in any other country in the EU.

But a hard Brexit would change that. U.S. banks with U.K. subsidiaries may need to obtain a new license from regulators in every EU country they operate in, which would disrupt operations.

Speaking of the big banks, chief executives of some of the largest U.S. banks faced off with the House Financial Services committee for the first time since the financial crisis on Wednesday. Ahead of the standoff between congressional lawmakers and the CEOs, Bank of America (BAC) announced it was raising its minimum wage for employees to $20 an hour. How convenient. J.P. Morgan Chase also announced efforts to hire more women at the executive level. Again, how convenient.

The focus on the big banks and financial institutions will only heighten in the coming days, as the financial sector will begin, in earnest, the Q1 earnings season. JP Morgan, PNC Financial (PNC), and Wells Fargo (WFC) will all report Friday morning, and then Citi (C) and Goldman will report Monday morning. Below is a chart of the EPS forecast and changes to those forecasts for some of the biggest banks set to report earnings.

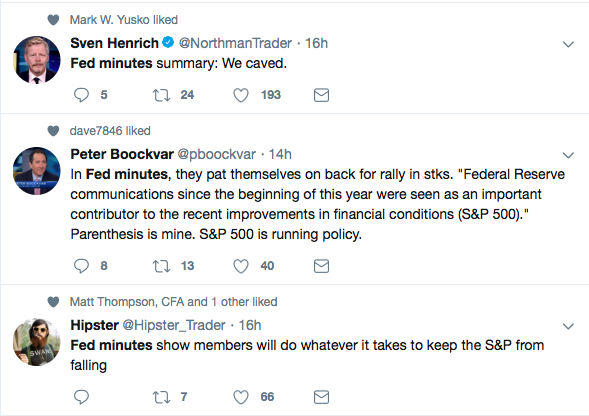

When it comes to the more important discussions on the big banks, it doesn’t get any bigger than the focus on the central bank or FOMC, here in the United States. Since the Fed decided to pivot from a period of rate hikes to no hikes forecast in 2019, the global equity markets have rallied along side bonds. The Federal Reserve’s decision in March to cease raising interest rates this year was driven by unease over the U.S. and global economies and surprisingly subdued inflation, according to minutes of the pivotal central bank meeting.

On the Fed’s list of worries: Sluggish U.S. growth early in the new year, a weaker global economy, the messy attempt by the U.K. to leave the European Union and festering trade tensions between the Trump administration and China.

“A majority of participants expected that the evolution of the economic outlook and risks to the outlook would likely warrant leaving the target range unchanged for the remainder of the year,” the minutes said.”

It was rather fitting that the FOMC March minutes were released the same day as the latest Consumer Price Index was released by the government. Why? Well within the Fed minutes, the Fed obviously discussed the notion of inflation or lack thereof within the economy.

“It was noteworthy that [inflation] had not shown greater signs of firming in response to strong labor market conditions and rising nominal wage growth, as well as to the short-term upward pressure o prices arising from tariff increases,” the minutes of the March 19-20 meeting said.”

At the March meeting, the Fed also announced it would stop selling off assets in its $4 trillion portfolio of government and mortgage-related bonds by September, another move aimed at shoring up the economy and ensuring stability in the U.S. banking system.

The minutes revealed a debate inside the Fed about when the bank should resume purchases of Treasurys after it ends it balance-sheet runoff.

Several wanted to resume purchases “relatively soon,” the minutes showed, but “some” preferred to let the average level of reserves decline naturally for awhile in the hopes that it would give the Fed a sense of underlying demand by banks.

With the banks, Fed, rates and inflation in focus, Finom Group’s chief market strategist offered the following on the subjects:

This is still probably the worst led FOMC that I’ve been forced to contend with since 1998. The stumbles around messaging Fed policy and outlook have been atrocious and lack the sophistication of former Fed Chairs and governing Presidents. I think what preceded the current board of governors and the impetus to elevate and highlight communications between the FOMC and broader investing public was well intentioned, but also demanded constancy. Unfortunately, as the political leadership changes in government, so does the Fed Chair and not every Fed Chair has the same capabilities or expertise. Clearly, the residing Fed Chair leaves much to be desired with regards to communication. I don’t want to decipher whether or not the Fed Chair simply doesn’t care what the public thinks because the FOMC knows and will act in the best interest of the economy or the Fed Chair is simply lacking for effective communication. That’s not a priority I wish upon myself.

At the end of the day and despite what you might here on CNBC or see on Twitter, the Fed did the right thing… there’s no inflation in the economy. Moreover, there could never be. The consumer drives the economy and there’s a tipping point in each and every economic cycle for which the consumer says “enough”! It happens in each expansion cycle and is highlighted within the trend of yields.

In each of the expansion cycles since the failed inflation policies of the 1980s, the 10-yr. Treasury yield has failed to achieve its previous expansion cycle highs. For the previous expansion that began in 2002 and lasted until 2007, the 10-yr yield high was roughly 5.5%. Today, in the current expansion that began back in 2009, we can’t even achieve 4% yields. The same exercise can be performed for the modern era and yields the same result, shy of the 1980’s errand monetary policies. In a consumer driven economy, all rates eventually go to zero; it’s just a matter of when.

While the media sensationalizes all things uttered and exercised at the Fed, the reality is the Fed is only attempting to extend that which it knows inherently will eventually occur. To that extent, the Fed is always ‘threading the needle”. The Fed is all too knowledgeable about the federal deficit and it’s own inability to buffer future economic turmoil. With that in mind, the Fed is caught between a rock and a hard place, but what else is knew for the Fed that is constantly combatting a Federal government that has limited to no fiscal spending restraint. So while the masses of public scrutiny always happen to fall upon the Fed’s head, the reality is the Fed can only do so much to react to economic issues, and that’s all the Fed actually does, react. The Fed does not equal causation folks; the Fed is merely a reactive measure to adversity.

With all that being said about the Fed and the notion of inflation, which more appropriately would be characterized as reflation, the latest Consumer Price Index validates the Fed’s pivot to a more dovish stance. Americans paid more for gas and rent in March, but broader inflationary pressures remained tame amid a slowdown in the economy early in the New Year.

The consumer price index jumped 0.4% in March to mark the biggest increase in 14 months, the government said Wednesday. Over the past year, the cost of living has increased 1.9%, up from 1.5% in February.

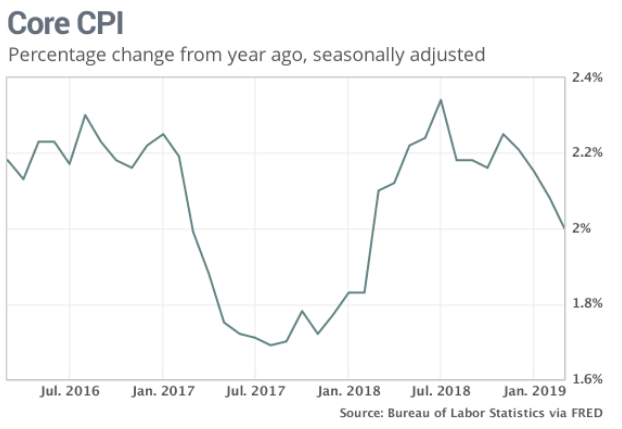

Three-fifths of the increase in March stemmed from higher energy prices, mainly gasoline and electricity. If the volatile food and energy categories are stripped out, so-called core consumer prices rose a scant 0.1%. Additionally, the more closely followed core measure slipped again to a 12-month pace of 2% from 2.1%. That’s the lowest level in a year.

Also with respect to where prices fell for consumers in March, they fell for clothes, used vehicles and airline fares. Apparel prices fell a seasonally adjusted 1.9% in what would have been the biggest decline since 1949, but economists said it’s likely a result of major changes in how the cost of clothing is calculated. Actual (unadjusted) clothing prices were basically unchanged.

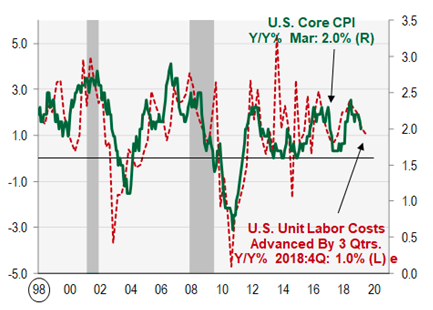

After taking inflation into account, hourly wages for American workers dropped 0.3% in March. They’ve risen 1.3% in the past year, down from 1.9% in the prior month. Although wages are still rising YOY, they are rising at a slower pace when we review the Unit Labor Costs.

March’s CPI report is good news for prolonging the business cycle as slowing ULCs suggest core inflation remains tame.

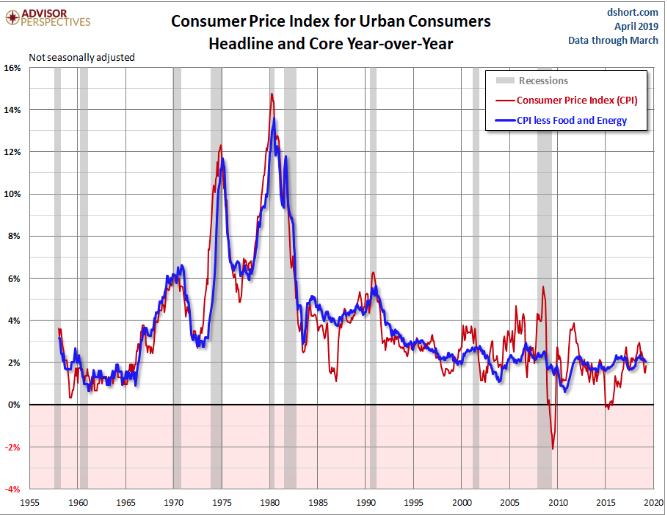

In referring to Seth Golden’s previous comments on the notion of inflation and what happens to rates and prices in a consumer driven economy over time, the following chart of historic CPI serves to validate the commentary:

As shown in the chart above, shy of the errand policies of the 1980s, prices only edge lower over time.

Regardless of what stage of the reflationary economic cycle we may find ourselves, economists will have a wide range of views on the subject matter. But one of Finom Group’s more favored perspectives on the economy and markets is Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research.

Yardeni is of the belief that the economy is slowing to a period of trend-growth, which is also constructive for further equity market gains. He suggests that the market swoon in Q4 2018 was merely a reaction to errand Fed messaging, akin to what our very own Seth Golden has outlined on several occasions. In an interview with Barron’s Yardeni outlined his thoughts on the market, the Fed and the economy.

“The stock market slide, he argues, was brought on by Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s statement in October that interest rates were “a long way from neutral.” But with the Fed now having pressed pause on any rate hikes, Yardeni says the market has resumed its previous upward trajectory. He sees the S&P 500 hitting 3100 at the end of this year, and continuing to climb to 3500 about a year later.

“Typically bull markets are killed by recessions—not by old age—and recessions have historically resulted from credit crunches,” he says. “That’s when the system seizes up and not only dodgy borrowers lose access to credit, but even good borrowers find it very hard to refinance or to get funding.”

At the tail end of expansions after years of economic growth, it’s common to see consumer and asset price inflation. That leads the Federal Reserve to respond by raising interest rates. “In the past it’s kept going until something would break,” Yardeni says. But in late 2018, Powell and the Fed listened to the message that markets were sending and stopped before something broke and caused a credit crunch.

It’s a similar scenario to early 2016, when the Fed backed off its intention to raise interest rates four times that year. In the previous year oil lost the majority of its value, corporate earnings declined, credit spreads widened, and the S&P 500 fell more than 10%. “Then it all sort of ended once the Fed backed off its threat, just as we’ve seen it do now,” Yardeni says.

Not everyone shares the perspective offered by Ed Yardeni of course! Bleakley Advisory Group’s Peter Boockvar is one such economist who believes the slowing in the economy is not the minor blip that 2016 proved to be. And just to be clear, yes, Boockvar is one of the permabears in the economists/social media community whom is able to find flaws in just about every economic data point or market indicator. He also takes pride in prodding the Fed’s messaging and actions as shown in some of his latest Twitter rants.

“The stock market is assuming…things will improve in Q2 and throughout the second half,” he told CNBC in an interview Tuesday. “The bond market has a less-optimistic take on that, saying that the data is weak, and we’re going to reflect that right now in lower yields and inversions within the yield curve.”

The bond market is going to be right,” said Boockvar, who oversees $4.5 billion in assets as Bleakley’s CIO. “We’re in a slowdown that’s not just temporary, and I think that’s something that’s going to last throughout the year.”

As for this earnings season, he says that 70% of companies will beat estimates “because that’s always the case.” But that won’t sway him.

“I’m waiting to see the extent of those beats,” he explained. “And I think it’s more likely than not that we’re going to see a decline.”

Despite Boockvar’s negative view on the economy and earnings going forward, the asset manager is still long equities, but positioned defensively in the equity market.

“I have a bigger cash position of about 20%, north of 10% in gold and silver, “Boockvar told CNBC. “A lot of the stocks I own are more value oriented. That obviously hasn’t been that helpful when everyone rushes to growth, but it’s a way for me to get somewhat defensive.”

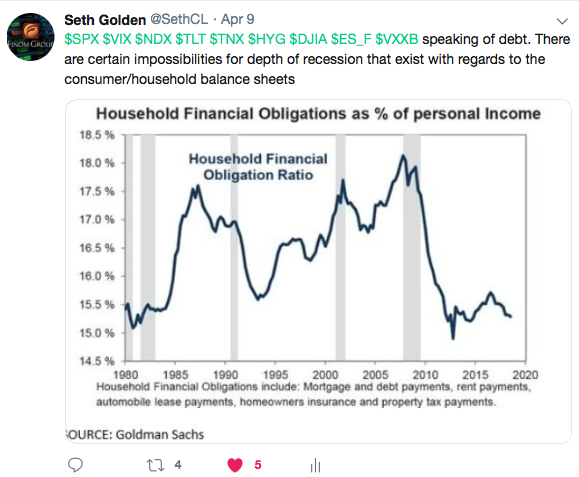

While we attempt to parse varying views on the market and economy, the two components are intertwined, eternally. Having said that, when a recession does come to pass the market may react more sharply than the economic decline would assume. Once again, Seth Golden outlines this point of a shallow economic recession in a recent tweet, highlighting the most favorable household debt to equity ratios in decades.

Essentially, tame consumer price inflation coupled with the fastest rise for wages in nearly a decade, consumers are in the best shape they have been for quite some time. Should an economic recession present itself, say in 2020, the strength of the consumer would likely serve to buffer the duration and slippage in economic activity. Having said that, Guggenheim separates the economies downturn in activity from the equity markets.

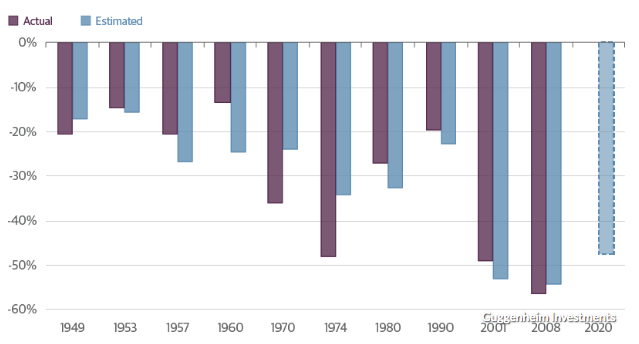

“The coming recession will be milder than past recessions — that’s the good news. The bad news is that the stock market is still likely to suffer a savage beatdown as an economic downturn sets in as early as 2020.

A lack of pent-up problems in the housing market and a well-capitalized banking system mean the economy is more resilient. That should be welcome news for risk assets, in the wake of March’s inversion of the yield curve.”

Nonetheless, Guggenheim Investments led by Scott Minerd, says that despite a relatively soft landing for the economy, equity benchmarks are likely to see a severe slump, partly due to lofty valuations and a lack of available fiscal and monetary policy tools. Guggenheim says the level of equity valuations going into the recession generally dictates the potential magnitude of the slide in stocks.

“Given that valuations reached elevated levels in this cycle, we expect a severe equity bear market of 40–50 percent in the next recession, consistent with our previous analysis that pointed to low expected returns over the next 10 years,” Guggenheim said.

U.S. equities are poised for a higher open on Wall Street Thursday, ahead of the release of both Initial Jobless Claims and the latest reading on the Producer Price Index. Both economic data sets are expected to tick higher.

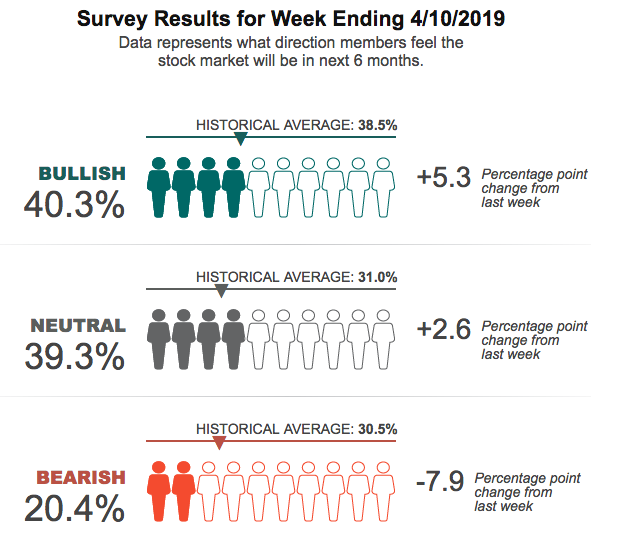

To reiterate, banks are set to begin reporting earnings on Friday ahead of the opening bell. Heading into the all-important earnings season, sentiment for equities has risen as viewed through the lens of the latest AAII survey.

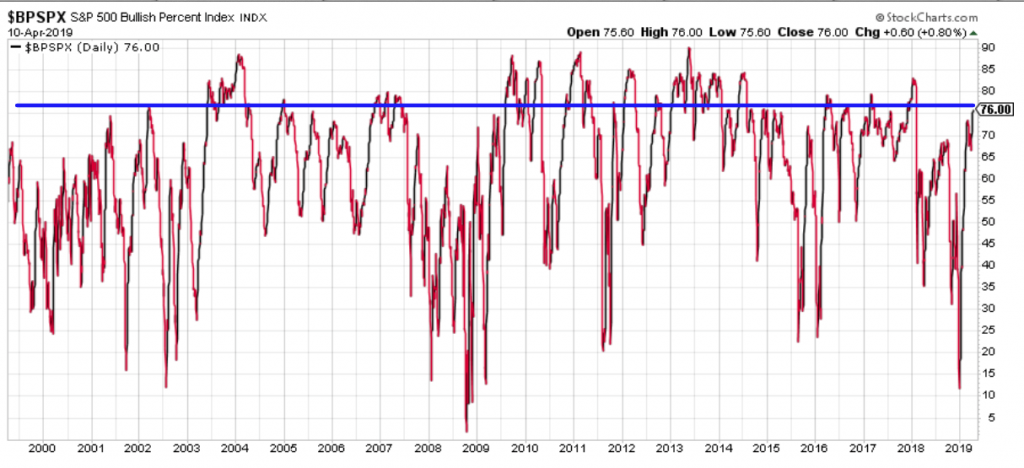

The bullish sentiment has finally risen above its historic average and bearish sentiment took a nosedive in the week that was. We’ll see if the survey can remain with bullish sentiment above 38.5%, as we dredge through the earnings season. In addition to the AAII survey we can more directly review market sentiment through the Bullish Percent Index. The BPI helps us to determine whether the YTD market rally is simply a bear market rally or the resumption of the bull market.

As we can see from the BPI, breadth was usually weaker in the 2000-2002 and 2007-2009 bear market rallies. The S&P 500’s Bullish Percent Index (breadth indicator) has now reached 76. This is a sign of healthy market breadth. All eyes on S&P 500 folks!