- Falls in equity prices and bond yields so far this week reflect fears that coronavirus cases outside China will mark the start of a wider outbreak that deals a blow to the world economy. For now, we envisage a moderate hit to global GDP growth of 0.5ppts this year, due almost entirely to the impact on China. But the economic effects of a severe pandemic could be as bad as those of the global financial crisis.

- There is still hope that the virus will be largely contained in China. We now expect GDP growth there to drop to -2% y/y in Q1 (compared to our pre-coronavirus forecast of +5%). Since China accounts for nearly 20% of the world economy, the direct effect of this alone will be to reduce world GDP growth in Q1 by 1.4ppts (to 1.6% from 3.0% previously).

- It is unclear how much of the lost output will be recouped, but with many factories now closed and some workers laid off, we expect there to be only partial catch-up at best. We have therefore cut our Chinese growth forecast for 2020 as a whole from 5% to 3%, which will reduce global GDP growth by 0.4ppts from our pre-virus forecast of 2.9% to 2.5%. This feels close to a best-case scenario as things stand.

- It has always been clear that the virus would have wider effects. And the rise in new cases outside of China points to a growing risk of a “global pandemic”, which has raised the feasible magnitude of the global economic impact significantly. There are five channels to consider when assessing how the economic disruption might spread.

- The first is the direct impact on affected economies due to measures taken to contain the virus. The second is the knock-on effect on other economies due to trade and supply chain links. Third is how people react, and the extent to which they decide to avoid leisure activities such as travel or shopping. Fourth is the financial market impact. And fifth is the fiscal and monetary policy response.

- Nobody knows how far the virus will spread or how severe it will become in the countries already affected. South Korea, Italy, Japan, Iran and Singapore account for 9% of global GDP. Adding that to China’s weight means that almost 30% of the world economy is now significantly directly affected.

- It is possible that the governments of the newly-affected countries will ultimately take draconian containment measures similar to those followed in China. But recent experience of only limited shutdowns in Japan and Italy suggests that the economic disruption is unlikely to be as severe. And even if containment measures became more aggressive, this would at least limit the risk of contagion elsewhere.

- Moreover, if cases started to spring up far and wide, without being able to be traced, then the authorities might consider that the horse had already bolted and there was little point in imposing travel restrictions or shutdowns. While that would be a terrible situation from a public health perspective, the direct economic effects would be smaller for each economy than they have been for China as a result.

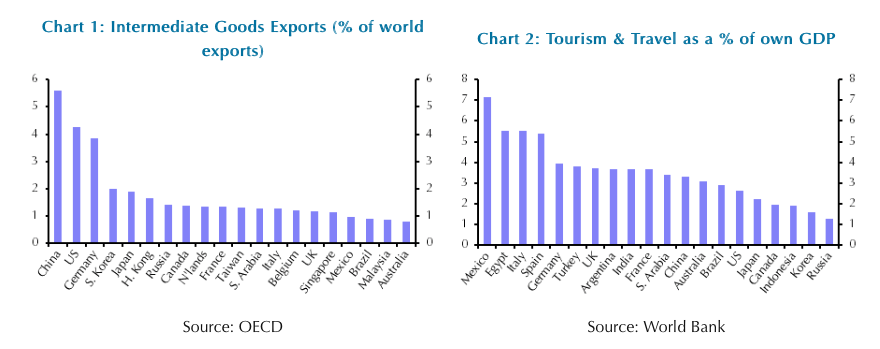

- But what of the indirect effects? The disruption to supply chains is very difficult to measure. China is the world’s biggest exporter of intermediate goods (see Chart 1) and hence arguably most important to global supply chains. So far, there is little or no direct evidence in the macroeconomic data of disruption to production outside Asia, although there are various reports that specific manufacturers (of cars in particular) in advanced economies are experiencing problems.

- Going forward, the US will be key to determining any likely supply chain disruption. While trade is a small share of its own GDP, the sheer size of the economy means that it is an important supplier and purchaser of components from other countries. Chart 1 shows that Germany, South Korea and Japan are also vital to global supply chains, which is worrying given that two of them have already been seriously affected.

- The third channel is the extent to which people self-isolate by avoiding public spaces, shops, cinemas, restaurants etc. Such effects are already clearly evident in China, where passenger traffic and car and property sales have slumped. And tourist arrivals to Thailand are down 50% y/y. Clearly, the further the virus spreads the bigger such effects will be. In the event of a pandemic, the worst affected economies would include those most dependent on tourism, including Mexico, Egypt and Italy. (See Chart 2)

- SARS offers a useful gauge of such effects. During the outbreak of 2003, there were very few factory closures and instead the effects on the economies in question stemmed from attempts by the public to self-isolate. GDP in the affected economies dropped very sharply, but then fully recovered. This might reflect the fact that, while capacity constraints prevent firms from fully making up for lost output, consumers face fewer limitations. Once the virus was contained, they may well go on a shopping spree or an unplanned weekend away, assuming that the disruption was not severe enough for them to lose income in the meantime.

- The fourth channel to consider is the financial market impact. Again, this has tended to be temporary during previous virus outbreaks and early experience in Chinese markets suggested that this time would be no different. But a further spread and mounting evidence of economic effects would clearly cause further falls in equity prices, with emerging markets likely to be most affected. They would also see their currencies fall sharply. Further falls in advanced economy bond yields would be possible, depending on whether central banks seemed poised to respond.

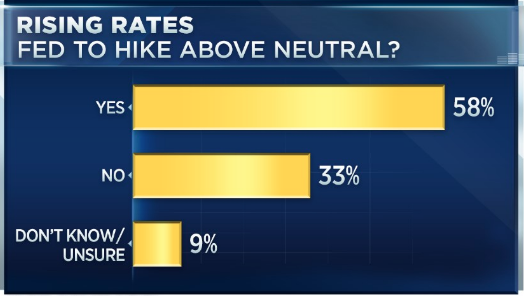

- This brings us to the fifth and final consideration, which is the likely policy response. So far, this has focused on targeted support for the affected parties, with the Chinese authorities providing subsidies and loans to the worst hit firms and to those involved in prevention and treatment of the coronavirus. Only a few small economies with close links to China have cut interest rates.

- Newly-affected economies will probably employ similar targeted fiscal support. Widespread interest rate cuts seem unlikely, but they could be used in the event of severe disturbance to economic activity or to financial markets. Note, for example, that recent experience suggests that the Fed is particularly inclined to respond to inversions of the yield curve with policy loosening. In cases where policymakers were willing and able to react quickly, the economic effects of the virus should be greatly reduced.

- On the whole, emerging economies seem most exposed to the effects of an escalating crisis. Many specialise in tourism or commodities production and downward pressure on their currencies due to rising risk aversion might well prevent them loosening monetary policy. Turkey and South Africa seem particularly vulnerable in this regard. But some advanced economies are also quite badly positioned, most notably Italy with its limited fiscal space and dependence on tourism. Meanwhile, Russia, Australia and Canada are at risk given the possibility of further falls in commodities prices.

- In conclusion, the best-case scenario now appears to be around a 0.4ppt hit to global GDP growth reflecting the damage to China’s economy. This would leave the annual rate at 2.5% in 2020. For now, we are assuming only a small additional hit through indirect effects, in the hope that cases elsewhere will be quickly brought under control. Our global growth forecast is therefore 2.4%. But there is huge uncertainty. If the hit to the economies affected so far was as bad as that to China, global GDP growth might fall to 2% this year. A global pandemic involving upheaval to trade and financial markets and currency crises in some countries could be as bad as 2009, when world GDP fell by 0.5%.

| EMERGING ASIA RAPID RESPONSE: Korea Rate Policy |

| Bank of Korea holds, policy support to be ramped up The Bank of Korea (BoK) made the unexpected decision to leave its main policy rate unchanged at 1.25% today, but with the coronavirus having a major impact on the economy, we think policy support will need to be stepped up in the coming weeks. Today’s decision was expected by 10 of the 28 analysts polled by Bloomberg. We were in the majority expecting a cut. The economic outlook in Korea has worsened significantly over the past week or so. A sharp rise in virus cases within Korea means that private consumption is set to slump as people avoid crowded places such as shops, restaurants and cinemas. There are currently 1261 cases confirmed, up from 29 at the start of last week. Other parts of the economy are also likely to be hit hard. Factory closures in China have led to production outages in Korea because of parts shortages and Chinese demand for Korean exports also looks to have been hit. The tourism industry, while a small part of the economy, is suffering as well. Overall, we are forecasting growth to slow to just 1.0% this year, from 2.0% in 2019. Inflation is not much of a concern at the moment – the headline rate was still below the Bank’s 2% target in January. The BoK is due to publish a statement and hold a press conference (via YouTube) over the next couple of hours, where it should give some more clues on its next move. It’s possible that the Bank thinks it is reaching the limits of what further rate cuts can do to support the economy. It may even start considering non-conventional monetary policy soon. Although the evidence from other countries that have tried quantitative easing suggests that it would have limited impact in Korea. Instead, the onus is likely to fall on fiscal policy. The government is currently drawing up a supplementary budget to address the economic fallout from the outbreak and we expect an announcement soon. |

Extended shutdown deepening economic contraction

China Economics Update:

- With normal activity taking longer to recover than seemed likely earlier this month, we now think that China’s economy will contract outright in year-on-year terms this quarter, for the first time since at least the 1990s. The leadership appears to be readying significant stimulus which should restore employment and output by the third quarter, but the hit to output during the first half of the year will still result in much slower annual growth.

- Official figures suggest that the coronavirus epidemic in China has followed a trajectory that tracks the more optimistic of projections from a month ago. The number of new reported infections outside Hubei has dropped to a handful each day. But evidence of an economic recovery has been less encouraging.

- The central government has for the past couple of weeks been urging provincial governments, employers and workers to resume normal economic activity. But the response has been lacklustre. While workplaces have in general reopened, most are operating well below usual capacity. Lengthy quarantine periods for those arriving from different provinces, and widespread reluctance to travel, are causing major dislocations for those reliant on migrant workers. Meanwhile, much discretionary spending appears to be at a standstill.

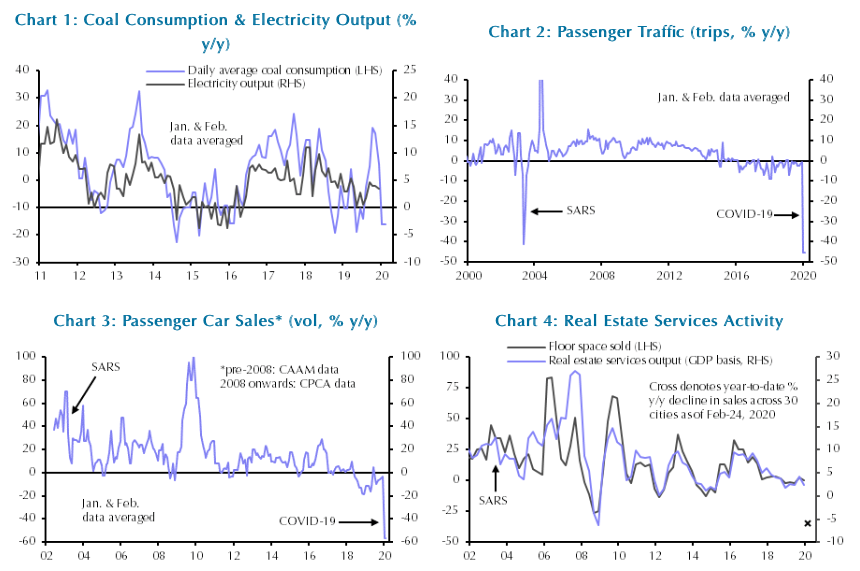

- Most monthly data for January and February won’t be released until mid-March. But a host of daily and weekly data illustrate the scale of the slowdown. For example, coal consumption at power plants suggests that electricity output, which is often a better guide to industrial activity than the headline industrial production figures, has contracted by 2-3% y/y this quarter. (See Chart 1)

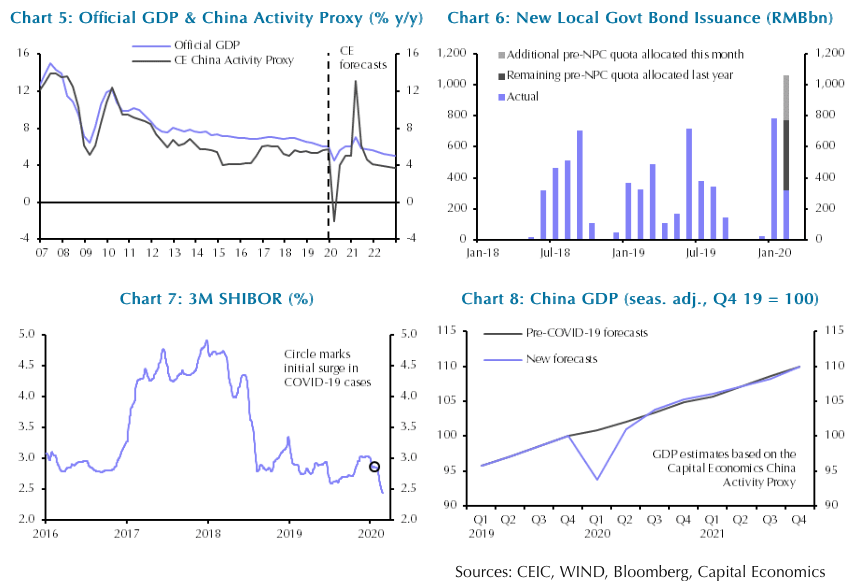

- That’s bad but not unprecedented: industry appears to have suffered a similar downturn in 2015. But this time the weakness is repeated across the economy. Free-flowing traffic in China’s cities illustrates that few have returned to work (though many office workers are working from home). Passenger traffic has collapsed. (See Chart 2) A sharp contraction in car and property sales suggests that broader consumption has been hit much harder than it was during SARS. (See Charts 3 & 4)

- We believe these indicators are now pointing to a 25% q/q annualised contraction in output this quarter. That would result in a fall in output of 2% y/y. (See Chart 5) We had been forecasting growth of +5.3% y/y in Q1 before the new coronavirus took hold.

- The slow speed at which economic activity is recovering suggests that weakness will extend into next quarter. The economic risks from extended disruption are non-linear. The longer it continues, the more likely it is that some firms won’t be able to pay workers, and will have to either cut pay, lay people off or shut down altogether. The self-employed and those working for SMEs make up 70% of China’s urban workforce. Recent surveys suggest that a third of SMEs only had enough liquid assets to continue paying employees for one month at the start of the outbreak.

- The central government is evidently concerned that the shutdowns risk causing lasting economic damage and is readying stimulus to counter it. The immediate focus has been targeted support for struggling firms, but policymakers have also encouraged a large ramp-up in local government bond issuance in preparation for an infrastructure spending splurge. (See Chart 6) The People’s Bank is also turning more proactive and has pushed interbank rates down by around 50 basis points. (See Chart 7) This implies a further reversal of efforts to cap debt ratios, but shoring up employment is now the priority.

- Assuming that policy support is further expanded, we expect output to return by Q3 to near the path it was on before the outbreak derailed activity. (See Chart 8) Some of the output lost in the first half of the year will be made up in the second half by firms running at a higher capacity than they otherwise would. But the lost output will not be fully recovered. We are cutting our full year forecast from 5% to 3%. The weaker base will then result in a rebound on paper in 2021 to 6.5%.

- According to a flash survey published yesterday by Focus Economics, three quarters of analysts expect the coronavirus to lower China’s growth this year by 0.8% pts or less, though it is unclear whether this refers to actual growth or official GDP. The downturn is unlikely to be fully reflected in the official figures. Precedent suggests that when economic targets are under threat, the statistics bureau fudges the numbers.

- While officials will have no choice but to acknowledge that Q1 was weak (we’ve pencilled in 4.5% y/y for the official data) we suspect that this will be made up later in the year to reach published annual growth of 5.6% (compared with 6.1% in 2019). That is what is needed to meet the government’s long-held goal of doubling real GDP between 2010 and 2020.