For a long time, I used to read Reminiscences of a Stock Operator almost every year. I don’t do that anymore, not because I find its lessons dated, but because I had it almost memorized so could direct my attentions elsewhere. The market’s behavior since the March 23rd bottom of 2191 to the 43% gain by July 2nd to 3130 has confounded most observers, from the novice investor to the most experienced and savvy, such as Stan Druckenmiller and Lee Cooperman. It appears that even Warren Buffett, who took advantage of every big bear market to pick up stocks cheaply, and who has always counseled investors to “be greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy,” ignored his own advice and sat this one out. In the middle of May, when the S&P 500 was trading around 2900, The Economist magazine’s cover was headlined “A dangerous gap” and subtitled “The markets v the real economy.” They were reflecting what most people then, and now, appear to believe: The market and the real economy had become “disconnected.” We were in the worst and fastest decline in economic activity since the Great Depression – 40 million were out of work due to a government mandated economic shutdown, leading to an unemployment rate not seen since the 1930s, yet stocks were inexplicably soaring. Surely, as many were, and still are, predicting, this would end badly and those who were chasing stocks higher were in for a nasty surprise sooner rather than later. Well, maybe, but I doubt it.

Let’s stipulate that neither I nor anyone else has privileged access to the future so no one knows for sure what is going to happen to stocks in the coming weeks and months. Still, there are some things that might help us sort through the differing opinions and probabilities. First, stocks go up most of time because the economy grows most of the time, about 70% for both time series. So if you knew nothing else and someone asked what the chances were that stocks would be higher in any given year, the answer would be 70%+. To put this in perspective, casinos are marvelously profitable and their house advantage varies by game from 1% to about 16%. In roulette, it is 2.7%. The stock market casino is a much better place to bet if your objective is to make money and not just to be entertained for a while. (There is a little known book called How to Gamble If You Must: Inequalities for Stochastic Processes which explores optimal strategies for negative expectations games such as roulette, where the longer you play the higher the probability you will lose all your money). Unlike many (most?) investors, casinos don’t shut down and refuse bets if they lose money at the roulette wheel. Knowing the odds are in their favor, they keep at it and ignore losing streaks (unless they think cheating is going on).

In his marvelous book, Winning the Loser’s Game, Charlie Ellis says that the reason we study market history is to protect our portfolios from ourselves. This is a very easy lesson to learn, but a very difficult one to observe in practice. Psychologists have documented that for most people a $1 loss is twice a painful as a $1 gain is pleasurable, hence the compulsion to stop the pain when stocks are collapsing by joining the selling and cutting your exposure.

The result of the panic out of stocks in March is that there is now all-time record cash in money market funds, and bond funds have seen huge inflows even as rates hover at levels not seen for thousands of years. In the US, bonds have never been more expensive in US history than in 2020. The S&P 500 yields 3x what the 10-year Treasury does, and dividends grow over time while treasury payouts do not. This is similar, in my opinion, to what happened around the bottom in 2009: People became risk and volatility phobic and most missed the great 10-year bull market. Those investors, though, for the most part did fine post 2009 if they kept their money in bonds because yields fell and bond prices rose. With rates so close to zero in the US, that happy outcome is unlikely to be repeated unless we go into a deflationary depression, which the Federal Reserve, with some help from Congress, is doing its best to make sure does not happen.

There is a reason one of most time honored adages in the market is “Don’t fight the Fed.” Every bull market has begun with the Fed cutting rates and every bear market has followed the Fed raising rates. It took a while for the Fed to marshal enough firepower to end the financial crisis of 2008/2009 but end it, it did. This time their response was immediate and overwhelming and stocks have responded accordingly. The reason comes down to what was called when I was an economics student about 50 years ago, the equation of exchange, MV=PQ: money x velocity = price x quantity. The pandemic and economic shutdown led to a collapse in money velocity as there was little to spend money on with so many businesses closed. Other things equal, P or Q or both would then collapse with velocity. PQ is equivalent to nominal GDP. So the Fed responded by expanding M, the money supply, at a record pace in an effort to stem the drop in GDP and set the stage for recovery. Some of that money is making its way into the real economy and the data indicate economic activity bottomed in the second quarter and things are improving. It also made its way into the markets, helping to lift stocks.

My friend Will Danoff, who runs the largest actively managed mutual fund in the US, the Fidelity Contrafund, and who has beaten the market over his more than 25 years at its helm, is fond of saying, as regards to investing in stocks, “Are things getting better, or are they getting worse?” Well, they are clearly getting better and that is expected to continue. Goldman Sachs expects annualized economic growth of 25% in Q3 after Q2’s decline, and 2021 growth of 5.8%. If that is correct, then GDP ought to be back to record highs some time in Q2 or Q3 of 2021.

The biggest problem with those who believe the market is disconnected with economic reality because the economic numbers still to come will be dreadful (and they will be) is that those numbers report the past and the market looks forward. The market predicts the economy; the economy does not predict the market. Stocks went down in the first quarter of this year and the first quarter of this year was a quarter of growth. Stock prices typically lead the economy by 4 to 6 months so it is, or ought to be, no surprise they have been headed higher. Why should they not be: Things are getting better not worse, earnings are bottoming and should begin to recover in Q3, the Fed has said they do not expect to raise rates for years, inflation is non-existent, interest rates provide no impediment to higher stock prices, and even valuations are not demanding at around 20x 2021 earnings given levels of inflation and rates.

Let’s go back to this idea that stocks at current levels are “disconnected” from the real economy and that presents a problem that stands in need of correcting. In order to say stocks are “disconnected,” one needs to have some idea of what the connection is between the market and the economy. The belief appears to be that stocks go up when earnings and the economy are going up and they go down when the economy is doing the same. So, in short, stocks and the economy are positively correlated. The problem with that view is that there is no evidence at all to support it, as a few minutes research demonstrates. The correlation coefficient of stocks to annual economic growth from 1930 through 2019 is .09, that is, no meaningful correlation at all. For rolling 10-year periods over the same time span, it is slightly negative. I am reminded of the quote of the now mostly forgotten British poet and classicist A.E. Housman, who likewise was confronted with a belief that had no basis. Housman said, “Three minutes’ thought would suffice to find this out; but thought is irksome and three minutes is a long time.”

None of this means, of course, that stocks won’t correct or that they might not descend into a new bear market. That depends on what happens in the future. In Reminiscences, Mr. Partridge is a grizzled market veteran, known as Old Turkey. After a strong move upward in stocks, a young investor who had recommended a stock that Old Turkey had bought told him the market was too high and he should sell and wait for the inevitable correction. Old Turkey demurred and when asked why, kept repeating “Well, it’s a bull market, you know.” Or as George Soros explained to me when I was short oil in 2008 as it soared to record levels (he was long), “You have forgotten something very important. You want to be long stuff that is going up, and short stuff that is going down.”

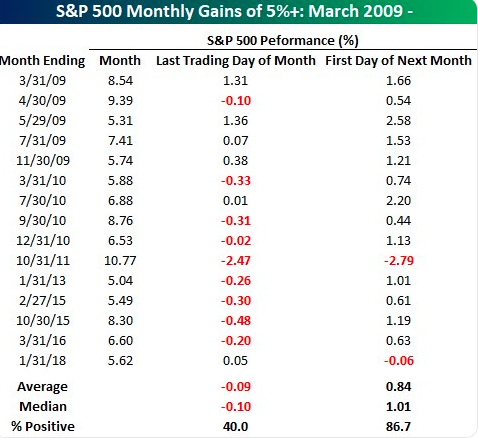

Stocks have been going up since late March. They have been following a pattern very similar to 2009: bottom in March, rally for two months, consolidate. In 2009, they then continued to go higher. What do I think? “Well, it’s a bull market you know.”

Bill Miller, CFA